Public Relations Services That Drive Real Business Results in 2025

Is your brand struggling to get noticed in an oversaturated market? According to a 2024 Cision study, companies with strategic PR see 3x higher brand trust scores compared to those relying solely on paid advertising.

Yet 67% of businesses still don't have a cohesive communication strategy.

Whether you're a startup founder looking for your first media mention or an enterprise CMO managing a reputation crisis, you'll find actionable insights backed by real industry data.

Table of Contents

Find the Right PR Service for Your Business

Media Relations

Get featured in top-tier publications and build credibility

Crisis Management

Protect your brand reputation during challenging times

Thought Leadership

Position your executives as industry experts

Media Relations & Press Outreach

Our media relations service helps you secure earned media coverage in top-tier publications, build relationships with key journalists, and craft compelling stories that resonate with your target audience.

- Press release writing and distribution

- Journalist relationship building

- Customized pitch development

- Interview coordination and preparation

Crisis Communication & Reputation Management

Our crisis management team helps you prepare for, navigate through, and recover from reputation-threatening situations with strategic communication and damage control.

- 24/7 monitoring and rapid response

- Crisis response protocols and planning

- Stakeholder communication strategies

- Long-term reputation recovery planning

Content Strategy & Thought Leadership

Our thought leadership service positions your executives as industry experts through compelling content, speaking opportunities, and strategic commentary on industry trends.

- Executive positioning and profiling

- Bylined articles and white papers

- Speaking engagement opportunities

- LinkedIn optimization and content strategy

What PR Actually Does (And Doesn't Do)

Let's clear up the biggest misconception first: PR is not advertising. You're not buying guaranteed placement or controlling the message completely.

Instead, modern PR firms help you:

-

Build earned media coverage

Where journalists choose to feature your story because it's newsworthy—not because you paid for it. A feature in TechCrunch or Forbes carries significantly more credibility than a banner ad because readers trust editorial content 4-5x more than sponsored posts.

-

Manage your reputation proactively

Before issues become crises. This includes monitoring brand mentions, preparing response protocols, and maintaining positive stakeholder relationships.

-

Position executives as thought leaders

Through speaking opportunities, bylined articles, and strategic commentary on industry trends. When your CEO is quoted in The Wall Street Journal, it elevates your entire organization.

-

Navigate complex situations

From product recalls to executive departures, ensuring your message reaches the right audiences at the right time.

What PR Cannot Guarantee

Be wary of any firm promising:

Guaranteed placements

In specific publications (this violates journalistic ethics)

Immediate viral coverage

Earned media takes time

Complete control over your story

Journalists maintain editorial independence

Overnight reputation transformation

Trust is built gradually

The 6 Core Services Explained

1. Media Relations & Press Outreach

Build credibility through earned media coverage

What it includes:

Crafting press releases, building journalist relationships, pitching stories, coordinating interviews, and securing coverage in targeted publications.

When you need it:

Launching a new product, announcing funding, entering new markets, or establishing industry credibility.

Real example:

A B2B SaaS startup we worked with secured 12 tier-1 media placements in 6 months, resulting in a 340% increase in qualified demo requests. The key was identifying a unique data angle that tech journalists couldn't ignore.

Average timeline:

3-6 months to see consistent results. First placements often happen within 4-8 weeks.

Red flags:

Firms that blast generic press releases to hundreds of journalists (spray-and-pray doesn't work in 2025). Quality outlets now penalize companies that send irrelevant pitches.

2. Crisis Communication & Reputation Management

Protect your brand when it matters most

What it includes:

24/7 monitoring, crisis response protocols, stakeholder communication plans, and damage control strategies.

When you need it:

Data breaches, negative reviews going viral, executive misconduct, product safety issues, or social media backlash.

Real costs of poor crisis management:

United Airlines lost $1.4 billion in market value after their 2017 passenger-dragging incident. Proper crisis PR could have significantly reduced the damage.

Critical first 24 hours:

How you respond in the first day determines whether an issue becomes a manageable incident or a reputation-defining crisis. Our crisis teams provide:

- Immediate holding statements (within 2 hours)

- Stakeholder identification and outreach

- Social listening and sentiment tracking

- Executive media training for interviews

- Long-term reputation recovery planning

Investment range:

Retainer-based crisis support typically costs $5,000-15,000/month for proactive monitoring, with incident response billed separately at $15,000-50,000+ depending on severity.

3. Content Strategy & Thought Leadership

Position your executives as industry experts

What it includes:

Executive positioning, bylined articles, white papers, blog strategy, speaking opportunities, and LinkedIn optimization.

Why it matters:

B2B buyers consume an average of 13 pieces of content before making a purchase decision (Forrester, 2024). Your executives' insights can be the content that tips the scale.

Content types that perform best:

-

Original research & data studies: Generate 3x more backlinks than opinion pieces

-

How-to guides addressing specific pain points: Rank for long-tail search terms

-

Industry trend predictions: Position your brand as forward-thinking

-

Contrarian takes (when backed by evidence): Drive social engagement and discussion

Distribution channels:

- Industry publications (Forbes, Inc., industry trade magazines)

- LinkedIn (executives with 5,000+ followers get 10x more reach)

- Speaking slots at conferences and webinars

- Podcast interviews (850,000+ active podcasts in 2025)

Timeline:

Building genuine thought leadership takes 6-12 months. Quick wins include LinkedIn optimization (2-3 weeks) and securing podcast interviews (4-8 weeks).

4. Digital PR & SEO Integration

Boost your online presence and search rankings

What it includes:

Link-building through earned coverage, digital newsroom management, influencer partnerships, and online reputation monitoring.

The SEO connection:

Every high-authority media placement that links back to your site improves your domain authority. A single link from a DR80+ site like Forbes can be worth $1,000-5,000 in SEO value.

Modern digital PR tactics:

-

Newsjacking: Inserting your perspective into trending stories (requires quick turnaround—same-day response)

-

Data-driven campaigns: Creating original research that journalists naturally want to cite

-

Digital press kits: Multimedia assets that make it easy for journalists to cover your story

-

Influencer partnerships: Working with industry experts who have credible audiences (not just follower counts)

Measurement:

Track referring domains, domain rating improvements, organic traffic from PR, and branded search volume increases.

5. Investor & Financial Communications

Build trust with stakeholders and investors

What it includes:

Earnings announcements, investor presentations, roadshow support, regulatory filings (in coordination with legal), and shareholder communications.

Who needs this:

Public companies (mandatory), pre-IPO companies (highly recommended), and late-stage startups seeking Series B+ funding.

Critical compliance note:

Financial PR has strict regulatory requirements (SEC rules, quiet periods, material disclosure obligations). Never work with a firm that doesn't have dedicated financial communications experience if you're publicly traded.

Investor perception impact:

Companies with strong IR communication trade at higher multiples. A 2023 Brunswick Group study found that effective investor relations can increase market cap by 5-15% through improved transparency and credibility.

6. Internal Communications & Employee Engagement

Turn your employees into brand ambassadors

What it includes:

Town halls, internal newsletters, change management communication, culture initiatives, and crisis communications to employees.

Why it matters:

Your employees are your best brand ambassadors. Companies with engaged employees see 21% higher profitability (Gallup). Poor internal communication during mergers, layoffs, or leadership changes can destroy morale and trigger unwanted turnover.

Common scenarios:

- Organizational restructuring announcements

- Executive leadership changes

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Layoff communications (requires extreme sensitivity)

- Return-to-office policies (hot topic in 2025)

Best practice:

Internal communication should happen before external announcements. Employees should never learn major news from Twitter or the media.

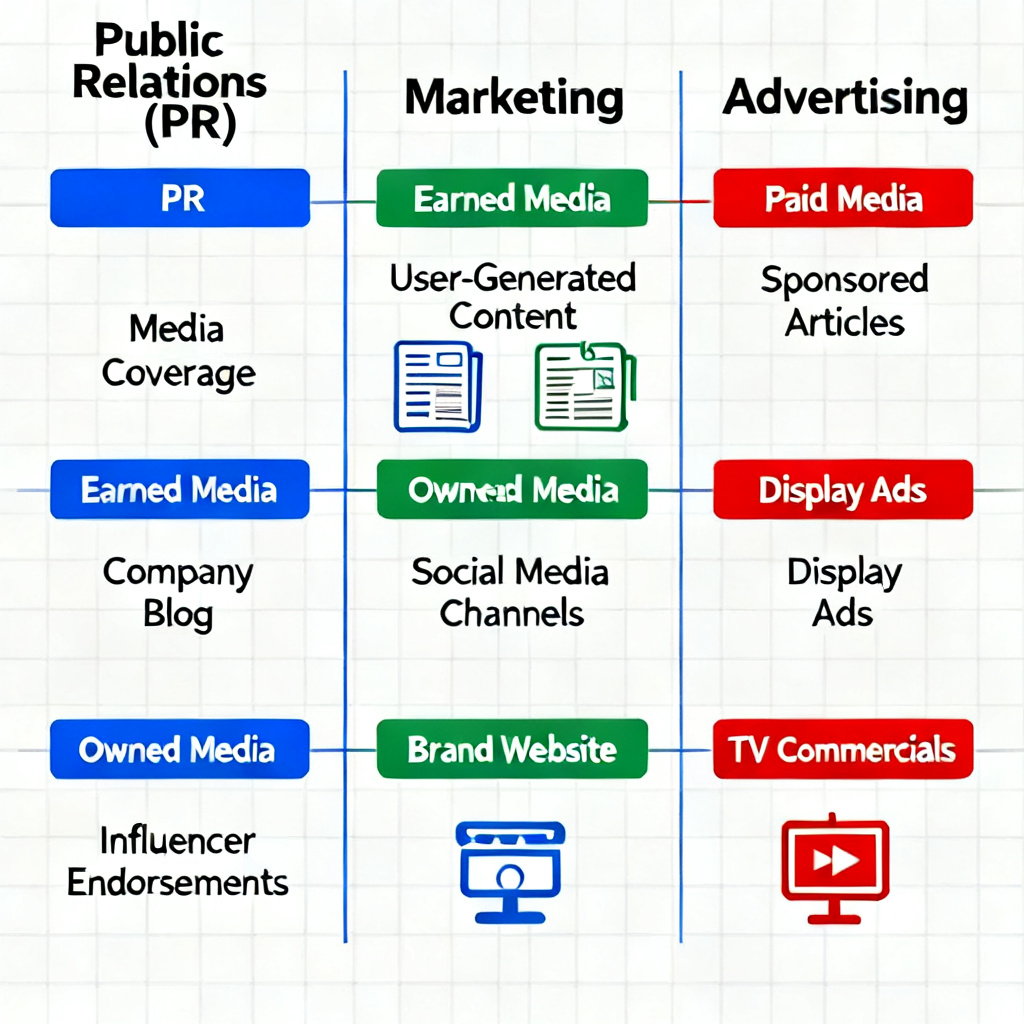

PR vs Marketing vs Advertising: Key Differences

Confused about where PR fits in your communication stack? Here's the breakdown:

| Aspect | PR | Marketing | Advertising |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Earned media (free placement) + agency fees | Mixed (content, campaigns, tools) | Paid placements |

| Control | Low (journalists decide final story) | Medium (you control message) | High (you control everything) |

| Credibility | High (third-party validation) | Medium (branded content) | Low (everyone knows it's paid) |

| Timeline | 3-6 months for results | 1-3 months for campaigns | Immediate when budget allocated |

| Best for | Building trust, managing reputation | Generating leads, educating market | Driving direct response, awareness |

| Longevity | Long-lasting (articles stay published) | Campaign-dependent | Ends when budget runs out |

The reality:

Most successful companies integrate all three. PR builds credibility that makes your marketing more effective and your advertising more trusted.

Pricing Guide: What to Expect

PR services vary widely in cost based on scope, market, and firm reputation. Here's what's realistic in 2025:

Monthly Retainer Models

Boutique Firms

(1-10 people)

-

Basic media relations: $3,000-7,000/month

-

Comprehensive PR: $7,000-15,000/month

Best for: Startups, small businesses, focused campaigns

Mid-Size Firms

(10-50 people)

-

Standard program: $10,000-25,000/month

-

Multi-service program: $25,000-50,000/month

Best for: Growth companies, regional campaigns

Large Agencies

(50+ people)

-

Corporate program: $30,000-100,000+/month

-

Global enterprise: $100,000-500,000+/month

Best for: Public companies, multinational corporations

Project-Based Pricing

Press release writing + distribution

$1,500-5,000

Crisis response (one-time)

$15,000-50,000

Product launch campaign (3 months)

$20,000-60,000

Thought leadership program (6 months)

$35,000-80,000

What Influences Price

Geographic scope

Local (cheapest) < National < Global (most expensive)

Industry complexity

Consumer products (simpler) < B2B tech < Healthcare/Finance (most complex)

Turnaround requirements

Standard < Rush (often 50-100% premium)

Firm reputation

Unknown firms < Award-winning agencies

Results track record

New firms < Proven portfolio of placements

Budget Red Flags

Too low

Any firm offering "comprehensive PR" for under $3,000/month is likely using automated tools, junior staff exclusively, or overpromising. Quality media relations requires experienced professionals who command market-rate salaries.

Too high without justification

If you're paying $50,000+/month, you should see detailed reporting, senior-level attention, and measurable results. Demand transparency on how time is allocated.

PR Budget Calculator

Get an estimate of what you should budget for PR services based on your needs:

Estimated Monthly Budget

$10,000 - $25,000

This estimate is based on industry averages for a mid-size firm handling national PR with media coverage and thought leadership goals.

How to Measure PR Success

The days of "PR is unmeasurable" are over. Here are the metrics that actually matter:

Tier 1: Media Impact Metrics

-

Number and quality of placements: Track tier (local/national/international) and reach

-

Sentiment analysis: Positive, neutral, or negative coverage

-

Share of voice: Your brand mentions vs competitors in target publications

-

Message pull-through: How often your key messages appear in coverage

-

Estimated ad value equivalency (AVE): Rough estimate of what the coverage would cost in advertising (note: this metric is controversial but clients still request it)

Tier 2: Business Impact Metrics

-

Website traffic from PR: Use UTM parameters to track referrals from coverage

-

Domain authority improvements: Monitor Moz DA, Ahrefs DR from earned backlinks

-

Branded search volume: Increases in people searching for your company name

-

Lead generation: Demo requests, contact form submissions after major placements

-

Sales pipeline influence: Track opportunities that mention media coverage in discovery calls

Tier 3: Reputation Metrics

-

Brand health surveys: Quarterly tracking of awareness, favorability, purchase intent

-

Crisis avoidance: Near-misses and issues successfully managed before they escalated

-

Executive profile growth: LinkedIn followers, speaking invitations, interview requests

-

Stakeholder sentiment: Employee, investor, customer perception tracking

Tools for Measurement

Media monitoring

Meltwater, Cision, Mention ($500-5,000/month)

Analytics

Google Analytics 4 (free), proprietary PR dashboards

Social listening

Brandwatch, Sprout Social ($200-2,000/month)

SEO tracking

Ahrefs, SEMrush ($100-500/month)

Realistic Expectations

First 3 months

Relationship building, initial placements in tier 2-3 outlets, foundation setting

Months 3-6

Regular coverage cadence, tier 1 placements beginning, measurable website traffic increases

Months 6-12

Strong results across all metrics, thought leadership positioning established, clear ROI demonstration

12+ months

Industry authority status, proactive journalist inquiries, crisis resilience proven

Red Flags When Hiring a PR Firm

Watch out for these warning signs:

Guaranteed Placement Promises

Why it's bad:

Ethical journalists never promise coverage. Any firm guaranteeing placements is either lying or engaging in pay-for-play arrangements that violate journalistic standards.

What to ask instead:

"Can you share examples of placements you've secured for similar clients, and explain your pitch strategy?"

"Spray and Pray" Approach

Why it's bad:

Blasting the same generic press release to 500 journalists gets you blacklisted. Modern media relations is about targeted, personalized pitching.

What to look for:

Firms that talk about journalist research, customized pitches, and relationship-building.

No Industry Experience

Why it's bad:

Healthcare PR requires different skills than fashion PR. Regulatory knowledge, journalist networks, and message framing all differ by industry.

What to ask:

"Show me three examples of campaigns you've run in my specific industry, including challenges you faced."

Opaque Pricing or Hidden Fees

Why it's bad:

Vague contracts lead to scope creep and unexpected bills.

What to require:

Detailed scope of work, clear deliverables, explanation of what's included vs. additional costs.

No Clear Reporting Structure

Why it's bad:

You can't improve what you don't measure. Firms that don't provide regular metrics are hiding poor performance.

What to expect:

Monthly reports with media placements, reach data, message analysis, and next-month strategy.

Team Turnover

Why it's bad:

If your account changes hands every few months, relationships (the core of PR) never develop.

What to ask:

"What's your average account team tenure? Who will be my day-to-day contact, and how often does that person change?"

Overpromising Speed

Why it's bad:

"We'll get you in Forbes next week" is usually a lie. Earned media requires relationship building and the right story angle.

Realistic timeline:

4-8 weeks for first placements, 3-6 months for consistent tier-1 coverage.

PR Firm Evaluation Checklist

Relevant experience in your industry

Proven media relationships with your target outlets

Senior team members actively working on your account

Transparent pricing and detailed scope of work

Clear reporting structure and measurement methodology

Strong communication skills and responsiveness

Positive client references and case studies

Alignment with your company culture and values

Case Studies: Real Results

B2B SaaS Startup Funding Announcement

Challenge:

A Series B SaaS company had $45M in funding but zero media presence. Their previous attempt at PR generated one local newspaper mention.

Strategy:

- Conducted data analysis to identify unique market trend their product addressed

- Created original research report with compelling statistics

- Identified 15 target journalists who regularly covered the space

- Coordinated exclusive embargo with TechCrunch for primary story

- Followed up with customized pitches to tier-2 outlets highlighting different angles

Results:

- 23 media placements in 6 weeks, including TechCrunch, VentureBeat, and Forbes

- 185,000 website visits from media referrals

- 1,240 demo sign-ups attributed to PR (17x normal rate)

- $340K in closed revenue directly tracked to media coverage

- Domain authority increased from 32 to 47

Investment:

$35,000 (3-month campaign)

ROI:

9.7x

Consumer Brand Crisis Management

Challenge:

A food brand faced potential recall after social media posts showed possible contamination. Negative sentiment was spreading rapidly (12,000 negative mentions in 24 hours).

Strategy:

- Activated crisis team within 90 minutes of issue identification

- Issued immediate holding statement acknowledging awareness and investigation

- Coordinated with QA team to verify scope (3 batches affected)

- Voluntary recall initiated with transparent communication

- Proactive outreach to food safety journalists with detailed facts

- Social listening team responded to every customer concern personally

- CEO video message released within 36 hours with corrective actions

Results:

- Negative sentiment peaked at 18 hours, then declined sharply

- Zero class-action lawsuits (typical in similar incidents)

- Brand favorability dropped only 8% (vs. industry average of 25% in recalls)

- Recovered to pre-crisis sentiment levels in 11 weeks

- Several journalists praised transparent handling in coverage

Investment:

$42,000 (crisis response + 8-week recovery program)

Avoided costs:

Estimated $2-5M in legal fees, lost sales, and long-term reputation damage

Executive Thought Leadership

Challenge:

A fintech CFO was brilliant internally but unknown externally. Company needed credibility boost before Series C fundraising.

Strategy:

- Optimized LinkedIn profile with clear positioning statement

- Published bylined articles on financial trends in industry publications

- Secured podcast appearances on three top finance podcasts

- Coordinated speaking slot at Money20/20 conference

- Positioned for reactive commentary on breaking financial news

- Created regular LinkedIn content addressing CFO pain points

Results:

- LinkedIn followers grew from 420 to 8,300 in 9 months

- Published in CFO Magazine, American Banker, and Forbes.com

- Quoted in WSJ and Bloomberg articles as expert source (without pitching)

- 14 speaking invitations received

- "CFO credibility" cited by investors as factor in successful Series C raise

Investment:

$72,000 (9-month program at $8K/month)

Impact:

Contributed to successful $80M Series C at higher valuation than projected

Average increase in qualified leads

Media placements per campaign

Average ROI percentage

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to see PR results?

Short answer: 3-6 months for consistent, meaningful results.

Detailed timeline:

- Weeks 1-4: Strategy development, media list building, initial pitching

- Weeks 4-8: First placements typically appear (often tier 2-3 outlets)

- Months 3-6: Regular coverage cadence established, tier-1 placements

- Months 6-12: Thought leadership positioning solidified, proactive media interest

Beware of firms promising immediate results. Building authentic media relationships and positioning takes time.

What's the difference between in-house PR and agency PR?

In-house PR:

Pros: Deep company knowledge, always available, aligned culture

Cons: Limited industry connections, no outside perspective, single skillset

Best for: Large companies with ongoing needs (typically 1 in-house person per $50-100M revenue)

Agency PR:

Pros: Established media relationships, diverse experience, scalable resources

Cons: Learning curve on your business, potential account turnover

Best for: Startups, growth companies, project-based needs

Hybrid model: Many companies use an in-house PR director who manages agency partners. This combines strategic internal oversight with agency execution capabilities.

Do I need PR if I have a strong marketing team?

Yes, if:

- You want credible third-party validation (earned media beats paid advertising for trust)

- You're building thought leadership positioning

- You need crisis management expertise

- You're launching something newsworthy (funding, product, expansion)

Maybe not if:

- Your entire GTM strategy is performance marketing

- You're in a purely technical/B2D (business-to-developer) space where traditional media doesn't matter

- Your brand is consumer-focused with no need for credibility signaling

Best practice: PR and marketing should work together. PR builds credibility that makes marketing more effective.

What makes a good PR story?

Journalists look for stories that are:

- ✅ Newsworthy: Represents something new, different, or significant

- ✅ Timely: Connected to current trends or events

- ✅ Data-driven: Backed by research, statistics, or evidence

- ✅ Relevant: Matters to the publication's specific audience

- ✅ Accessible: Can be understood by their readers without jargon

- ✅ Visual: Has compelling photos, infographics, or video

❌ Not newsworthy:

- "Our product is great" (every company says this)

- "We won an award" (unless it's truly prestigious)

- "We hired someone" (unless they're a major industry figure)

- "We launched a feature" (unless it's genuinely innovative)

Can PR help with SEO?

Yes, significantly. Every high-quality media placement that includes a link back to your website:

- Increases your domain authority (Google's trust signal)

- Drives referral traffic from readers

- Creates brand awareness that boosts branded searches

- Builds topical authority in your industry

Real impact: Companies with active PR programs see an average 32% increase in organic search traffic over 12 months (BrightEdge, 2024 study).

However: PR should never be done only for SEO. Google penalizes manipulative link-building. Focus on earning genuine coverage, and SEO benefits follow naturally.

What's the best way to prepare for a media interview?

Before the interview:

- Understand the journalist's beat and recent articles

- Prepare 2-3 key messages you want to convey

- Practice bridging techniques to redirect to your messages

- Prepare specific examples and data points

- Know what topics are off-limits (coordinate with legal if needed)

During the interview:

- Assume everything is on the record unless explicitly stated otherwise

- Speak in soundbites (short, quotable sentences)

- It's okay to say "I don't know, but I'll find out and follow up"

- Never say "no comment" (sounds guilty; instead bridge to what you can discuss)

- Ask for clarification if a question is unclear

After the interview:

- Send any promised follow-up materials promptly

- Offer to fact-check technical details (not edit for messaging)

- Thank the journalist for their time

How do I handle negative press or a crisis?

Immediate actions (within 2 hours):

- Assess the situation objectively—is it a real issue or overblown?

- Assemble your crisis team (PR, legal, operations, executive leadership)

- Issue a holding statement acknowledging awareness

- Monitor social media and news coverage for spread

Within 24 hours:

- Determine the facts and your response strategy

- Draft detailed statement addressing the issue directly

- Identify key stakeholders and communicate to them directly

- Prepare executive for potential media interviews

Long-term recovery:

- Take concrete corrective actions (not just words)

- Communicate those actions transparently

- Monitor sentiment and adjust messaging as needed

- Rebuild trust through consistent, authentic behavior

Critical rule: Never lie or obscure the truth. Cover-ups always make crises worse. Transparency and accountability are your best tools.

When should a startup invest in PR?

Too early:

- Pre-product (unless you're a serial entrepreneur with a track record)

- Pre-product-market fit (focus on building first)

- Without a clear newsworthy angle

Right timing:

- After raising Seed/Series A funding (timing the announcement properly)

- At product launch with clear differentiation

- When you have interesting data or customer traction to share

- Before entering a competitive market (need awareness)

Budget rule of thumb: Allocate 5-10% of your marketing budget to PR, or expect to spend $5,000-15,000/month minimum for meaningful results.

How do I choose between PR firms?

Evaluation criteria:

- Relevant experience: Have they worked with similar companies in your industry?

- Media relationships: Can they demonstrate connections to your target outlets?

- Team seniority: Who actually works on your account (not just who sells)?

- Case studies: Can they show results similar to what you need?

- Cultural fit: Do you trust them and enjoy working together?

- Pricing transparency: Are costs and deliverables clearly defined?

- Reporting approach: How do they measure and demonstrate success?

Red flags during selection:

- Guaranteed placement promises

- Unwillingness to share references

- Vague answers about strategy

- Focus on their awards rather than your goals

- Pressure to sign long-term contracts immediately

Best practice: Start with a 3-month pilot program to assess fit before committing to longer terms.

Getting Started: Your Next Steps

If you've made it this far, you understand that effective PR is about building credibility, managing perception, and creating lasting relationships with media and stakeholders.

Startups and Growth Companies

Start with a focused 3-month program targeting 2-3 key announcements. Budget $5,000-15,000/month. Focus on product launches, funding announcements, or milestone achievements.

Established Businesses

Consider a comprehensive retainer program ($15,000-50,000/month) covering ongoing media relations, thought leadership, and crisis preparedness.

Enterprises

Engage a full-service agency with capabilities across media relations, crisis management, financial communications, and global reach. Budget $50,000+/month.

Questions to Ask Yourself Before Engaging a PR Firm

-

What specific business goal will PR help us achieve?

-

Do we have newsworthy content to share in the next 6 months?

-

Are our executives prepared to be public faces of the company?

-

Can we commit to 6-12 months (the realistic timeline for results)?

-

Do we have the budget for sustained effort ($36,000-180,000 annually)?

Our Expertise

With [X years] of experience across [industries], our team has secured coverage in [notable publications], managed [number] crisis situations, and helped [number] companies build lasting reputations.

We specialize in:

Contact Us

Ready to elevate your brand's reputation? Contact us for a complimentary strategy consultation where we'll:

- Audit your current media presence

- Identify newsworthy angles you may be overlooking

- Recommend a customized PR strategy

- Provide a transparent pricing proposal

Message Sent Successfully!

Thank you for contacting us. We'll get back to you within 24 hours.